This will probably be the shortest article ever because, in short, if it were possible to sit down and write a bestselling novel, wouldn’t every author do just that? According to Google, a writer simply needs to (1) have a big idea (simple—they grow on trees), (2) write with an audience in mind (always handy), (3) package the book to sell (definitely helps), and, my favorite, (4) use a female lead character, as there is a higher number of bestselling titles with female leads (okey-dokey). Interesting, Google. So can a writer set out to write a bestselling novel? That’s probably the wrong question. Here’s a better one.

Since I’ve represented (at this point) 53 New York Times bestselling novels, you’d think I’d know a thing or two about them. But honestly, it’s a wonderful surprise every time a client of mine hits the NYT list. (The latest was Shelby Van Pelt’s debut Remarkably Bright Creatures in May.) When talking bestsellers, James Patterson is probably the best person to interview. He has cracked the code for sure, given the number of works he has on the NYT list at any given time. But my answer to this question is no, a writer can’t really set out to write a bestselling novel. Over the years, I have observed a few things about bestsellers.

Observation 1: None of my clients set out to write one. They all began with a story that felt personal to them and that they were passionate about writing. My NYT-bestselling clients also said they started with the voice of the story. It was unique, clear, and, once found, natural to write.

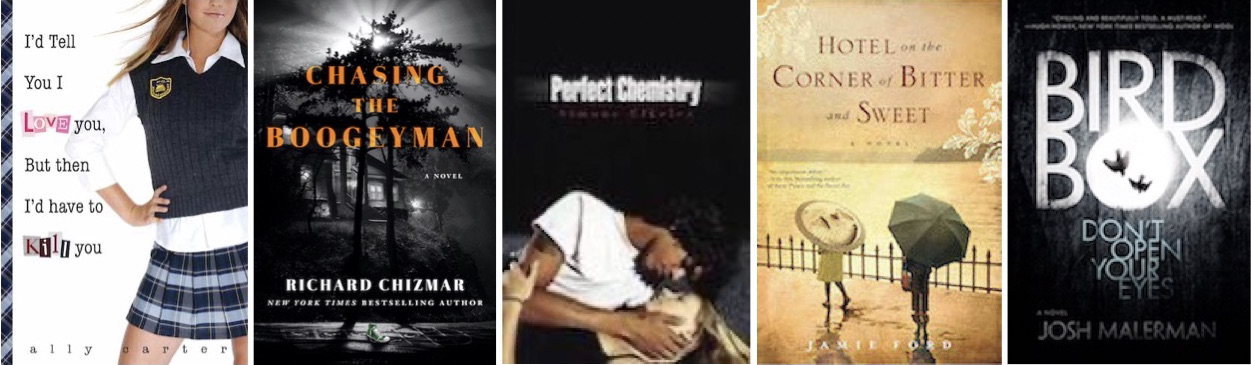

Observation 2: Not unlike what Google helpfully suggested, all NYT titles start with an original concept, so although there are no new stories under the sun, these works felt fresh and original to the readers who discovered the novels and then raved about them to other readers. Some examples:

- A 50-year old man searches for the woman he loved during WWII before his love was sent away to an internment camp. (Hotel On the Corner of Bitter and Sweet)

- A giant Pacific octopus helps unlock the mystery of what happened to the aquarium cleaning lady’s son thirty years ago. (Remarkably Bright Creatures)

- A teen who attends a school for spies funnels her skills into spying on her first crush while also navigating the world of espionage. (I’d Tell You I Love You But Then I’d Have to Kill You)

- A soulless woman nullifies the power of supernaturals such as vampires and werewolves with her touch and has to uncover why supernaturals are disappearing. (Soulless)

- A Chinese American teen secretly living below a newspaper company moonlights as the anonymous but wildly popular society columnist Dear Miss Sweetie, whose articles shake up the town. (The Downstairs Girl)

Observation 3: Although publishers try to create bestsellers, for a debut novel to hit the list, there is an intersection of what readers are wanting to read and market timing. Plenty of titles can have the right ingredients, full in-house support, and marketing dollars, yet they still won’t land on the list. In the end, the reading public decides (as well as the algorithm used by the New York Times, but that is a whole other article).

For me, a better and more interesting question is this: What would a bestselling story look like for you personally as a writer? Where is your intersection of concept, passion, voice, and unique characters? Is it possible to analyze bestsellers to see what makes them tick? Jodie Archer and Matthew L. Jockers do just that in The Bestseller Code. As reviewers point out, this book won’t teach you how to write a bestseller, but it will reveal some interesting stats concerning bestsellers and what they all seem to have in common. Would that info give you a fresh perspective on your own story or take you one step closer to writing a bestseller?

Only you the writer hold the answer to that question.

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.