Happy December! Wishing all our loyal newsletter readers a joyful holiday season. As extra holiday cheer, we are delivering our end-of-year stats early. Normally we make readers wait until January, so click now and enjoy. We’ve also been crunching some newsletter data, and those insights show that 2023 will ring in some change.

Had I been smart, I would have saved every newsletter created. Best that I can tell, we here at NLA have been delivering a monthly newsletter since 2008. That is basically a decade and a half of delivering insider content to help aspiring writers learn about publishing and navigate the industry. I’m not going to lie. Many a month I’ve been swamped, time crunched, and struggling to carve out the time to whip up an article. Sometimes it feels like an extra homework assignment on top of an already heavy workload. I would daydream about a final newsletter. But now that the time is possibly here, I feel a little melancholy. This has long been a part of my agenting life.

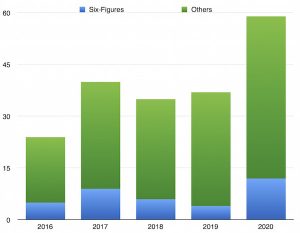

But in the end, stats tell a unique story. Although we’re proud of having over 7,000 subscribers, only about half ever open the email. Of that half, only 500-1,000 click on a link to read an article we are sharing. What’s clear is that we certainly have a loyal readership (and we heart you folks if you are reading this right now!), but in the end, that’s a lot of time, work, and content development on our part for so few eyeballs. Please do keep in mind that we crunched the data prior to our unexpected hiatus in mid-2022.

All this is to say with a heavy heart that it might finally be time to retire the newsletter. For the beginning of 2023, the newsletter will be on hiatus as we evaluate the cost-benefit ratio. We might retire it for good, or we might decide to relaunch it in the future with a new look, feel, and focus.

As we love stats, there was no way we were leaving our loyal readers without one last annual sum-up. I know it’s a fan favorite, so we are happy to oblige.

THE 2022 STATS

8,539 : Queries read and responded to. Down from 13,932 in 2022 and although this looks like a precipitous drop, NLA is leaner, more focused team now, and for personal reasons, both Joanna and I were closed to queries for long stretches of the year.

287 : Number of full manuscripts requested and read (down from 353 in 2021): 61 requests for Kristin, 227 requests for Joanna (who was an obvious reading rock star!). For me, 70% were referrals or requests made at a conference or pitch event as I was closed to queries for so much of the year. For Joanna, only 17% were referrals or conference/pitch-event requests.

64 : Number of manuscripts we requested that received offers of representation, either from us or from other agents/agencies (down from 111 in 2021). This might be an indicator of the burn-out happening across the industry, or it might just be a momentary adjustment.

4 : Number of new clients who signed with NLA (0 for Kristin—two years in a row, eep—and 4 for Joanna)

29 : Books released in 2022 (down from 37 in 2021 as it is now just Joanna’s and my client lists).

3 : Number of career New York Times bestsellers for Joanna (up from 2 in 2021)—extra congrats to her client Kate Baer.

54 : Number of career New York Times bestsellers for Kristin (up from 51 in 2021). So wonderful to see Jamie Ford on that list again and to celebrate Shelby Van Pelt hitting with her debut novel.

2 : Number of Today Show #ReadwithJenna Book Club picks (2 in one year, a first for Kristin’s career).

7 : TV and major motion picture deals (up from 5 from previous year, indicating Hollywood is still buying and buying a lot).

2 : TV shows in production (coming in 2023, Wool Saga on Apple+ and Beacon 23, both based on works by Hugh Howey).

109 : Foreign-rights deals done (slightly down from 126 in 2021 which shows there is some belt tightening going on, although 3 of those deals were with Ukraine publishers, bless them).

1 : In-person conference attended by Kristin (StokerCon in Denver, and lots of people had Covid afterwards but I was okay).

0 : Virtual conferences attended by Kristin.

0 : Physical holiday cards sent (our first year of Paperless Post for clients).

762 : Electronic holiday slideshow cards sent (up slightly from 736 in 2021).

Lots : Of wonderful days reading and appreciating creators.