(Just a note, this article was featured in our May 2019 Newsletter. Some references may not correspond with recent events. To receive our articles first, you can subscribe to our newsletter here.)

I have a confession to make: up until a few weeks ago, I didn’t know a lot about permissions. Sure, I could explain the clause in a publishing contract where it states that the author is responsible for securing permissions from third parties for use of third-party material in the author’s books. But I kind of assumed (or hoped) that if it ever came to it, the publisher would walk the author through the actual process. Not so. So when one of my authors wanted to secure permissions for some song lyrics she wanted to include in her upcoming release, we ventured down the winding road together. Here is what I learned:

- What do you need permission for? You need legal permission any time you want to quote or excerpt someone else’s work in your own. That can apply to anything from poetry to song lyrics and every magazine article or blog entry in between.

- The concept of “fair use” is murky. Isn’t there a law that states that you can use a percentage of someone else’s work for free? Not really. As Jane Friedman so smartly points out in her post A Writer’s Guide to Permissions and Fair Use , there is no defining rule about how much of someone else work is “OK” to use without permission. So your best bet is always to ask.

- Your publisher really isn’t going to help you. Publishing contracts specify that the author is responsible for securing all necessary permissions, and they mean it. It is the author’s job to figure out who to reach out to regarding securing permissions. Don’t expect your publisher to have a list of record executives’ email addresses or standard forms to fill out for such an occasion. This part of the process can require quite a bit of leg work in terms of tracking down the right individuals. Side note: agents won’t necessity be able to help either. While I’m always happy to advocate for my clients, I do not have the necessary connections to move this process along.

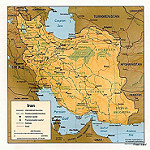

- There is a cost and it can be steep. Most of the people my author reached out wanted to know certain information such as print run and territory of distribution before calculating permission fees. They then based their fees accordingly, and they were notable. One of the terms I learned during this process was “favored nations,” which basically means that one party cannot be paid more than another. As it pertains to permissions, don’t think you’ll be able to strike a deal with a record company because you’re only using a few lines, for example, or that another company will give you a break because they like the premise of your story. The people you’re reaching out to are, in turn, advocating for their clients. They want to make sure that the content their clients made is respected in the marketplace, and that means fiscal compensation. And they pretty much have a going rate. The other thing to consider is that you have to pay regardless of how much money you’re making or if you’ve been paid your full advance or not.

- Permissions live with your work. If your book takes off, know that permissions requests will follow you. So far, from what I’ve seen, costs are associated with the publisher’s proposed print run and are limited to the territories requested. That means that if your book sells over whatever your publisher initially projected, you will have to pay permissions fees again. Same goes for every foreign license (and there are some caveats depending on whether or not a foreign publisher intends to keep the lyrics in English). In sum, this is not a one-and-done thing.

So what can you do? Think about how important any excerpts are to your writing. Can you write around them? Mention them in passing? For example, reference a well-known chorus that readers will be sure to get, if we’re talking about music? Your other option is to search public-domain offerings that will fit the bill. Works in the public domain can be used without permission.

Creative Commons Credit: F Delventhal